Three years ago, Racquel Racadio sat in her one-bedroom apartment on a warm summer evening writing a policy paper she wasn’t sure anyone would read.

But she plowed ahead anyway.

For much of her life – before working at Amgen – she had seen people dragged down by poor health, few choices and little hope. There was her time as a nursing assistant in a veteran’s hospital in Madison, Wisconsin helping men and women with broken bodies – some weeping because they couldn’t bathe themselves. There was the time at the free clinic in Milwaukee, Wisconsin where those without access to medicine – or who had ailments that medicine hadn’t reached yet – arrived daily. There was the time in radiology where patients diagnosed with cancer came, fearful their tumors hadn’t shrunk. Many were Black or Latino. Too many, she thought.

So, she sat alone on the carpeted floor, laptop balanced on the coffee table. Music played in the background. It helped her focus. She had put in a long day at Amgen – meeting about clinical trial site selections, managing projects and gathering feedback on protocol designs. The drive to do this work came from a sense of moral duty. It seemed like the right thing to do, consistent with one of Amgen’s core Values.

Racquel Racadio, who also has a background in public health policy, began writing the paper in 2017 that would become foundational for RISE and the push to diversify clinical trials. Photo: Shannon Faulk/Getty Images

Racadio had long wanted to make changes in the system. Now it was her chance to try and help establish a new way of doing things with a major company. She believed she could help diversify clinical trials at Amgen so the company could be a leader for change while also improving its scientific strategy approach as well as the business side. She also believed Amgen wanted to do better. This was her chance to help.

And so, she kept writing.

The Problem

Clinical trials have lacked diversity for decades and many believe this issue is rooted deeply in the history of abuse and neglect toward minority communities – and the Black community notably – dating back to the era of slavery.1 With a prevalence of cardiovascular disease and cancer among Black populations, for example, clinical trial diversity hasn’t kept pace with the population breakdowns.2

According to the Journal of the American Heart Association, overall enrollment population among trials showed 81% of the participants were White while just 4% were Black – despite Blacks accounting for 13% of the overall population in the United States.3

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration showed that, for clinical trials in oncology, the rates were even worse with only 2.74% of participants being Black. The same survey showed participation by Blacks in clinical trials for cardiovascular disease was at 2.5%.4

Furthermore, the non-profit journalism site, ProPublica, found that in trials for 24 of the 31 cancer drugs approved in the past three years, less than 5% of the subjects were Black.5

“We believe it is our duty to ensure that minority representation in cancer clinical trials is addressed,” said Sung Poblete, chief executive officer of Stand Up 2 Cancer, in a PharmaLive.com story last year. “Now, more than ever, better understanding of the role of biology in cancer treatment, advances in precision treatment, and development of new technologies demands that we also make significant improvements in diverse clinical trial participation.”

A year before Racadio wrote her paper, the issue was already being discussed informally among a handful of people in 2016 to discuss Amgen’s low rate of diversity in its clinical trials. Employees Willis Steele and Jude Ngang talked about it at a meeting of the Amgen Black Employee Network (ABEN) to discuss possible paths to raise awareness on the issue.

Ngang said the issue was personal for him.

Growing up in Cameroon before coming to the United States more than two decades ago, he said he took a circuitous route to the healthcare industry – first working for Amtrak as a machinist and then leaving to get a doctorate in pharmacy before working as a director of business performance at Amgen.

In his last year of pharmacy school, he said his mission became clear after he saw a drug get to market that was designed to reduce hypertension. The problem, he said, was an inordinate number of Blacks using the drug were still suffering from uncontrolled hypertension and could eventually experience major cardiovascular events such as strokes. He went back and saw the numbers: Very few Blacks were enrolled in the clinical trials.

“That medicine was approved and recommended in treatment guidelines to manage hypertension and yet Black people taking the medicine were still suffering from uncontrolled hypertension,” Ngang said.

Jude Ngang saw the issue of diversity in clinical trials as personal to him. He began meeting with Willis Steele in 2016 about trying to help Amgen diversify its clinical trials. Photo: Stacy Gleason

Like Racadio, he knew the change would need to start from within, so he began looking for work opportunities within pharmaceutical and biotech companies. Amgen hired him in 2016 and that’s when he met Willis Steele for the first time.

They spoke about the lack of diversity in clinical trials and about ABEN and what role it could play in moving Amgen forward. It was a moment where ABEN changed from being socially driven to more issues oriented.

Their first meeting about the topic was in a small conference room in Building 28 on the company’s main campus in Thousand Oaks, California. They discussed the barriers, possible solutions and the chances of success.

Willis Steele saw a need for diversity in clinical trials as an ongoing issue and one he saw as a problem dating back to the HIV/AIDS crisis. Amgen file photo

Rise Up

Steele had been troubled by the lack of diversity in clinical trials dating back to his time working in the Bronx (a borough of New York City) during the HIV-AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s.

He said the early treatments were based on clinical trials that involved gay white males. He said they fared well with the early drugs. Not so much with the Black men who took them, however.

“Their hair thinned out and fell out. Their nails turned black. Some had developed lipodystrophy,” Steele said. “It was clear that there was a problem – they hadn’t diversified the study group.”

He said the problems were systemic and larger than a single company. One critical aspect to clinical trials was that most companies relied on established locations that could pull participants together quickly. But many of those sites also featured predominantly homogenous populations.

This desire for efficiency were helping one group while letting minorities suffer and die.

Steele said it was important to make a difference where he was, so he and Ngang helped arrange for a panel discussion in February 2017 – a diverse panel featuring Black cardiologists and ethnically diverse researchers. It was also where they first met Racadio, who was a panelist at the event.

The panel got the attention of senior leadership at Amgen. Steele said he could see things starting to click with them.

“That’s when we knew there was hope this could go somewhere,” he said. “But we still needed to make the case on paper.”

Which is when they tapped Racadio to try build a foundation for the effort.

Five Pages of Foundation

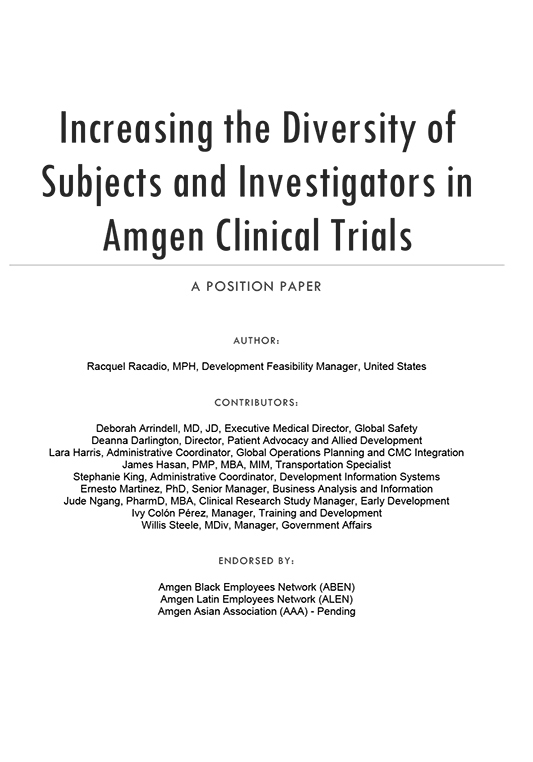

The paper she wrote in her living room on the floor laid out the problems. It suggested goals, including sponsoring initiatives and training programs to develop diversity among investigators, expanding clinical trial sites and expanding patient recruitment from diverse communities. She also suggested starting with oncology.

Willis said the paper, at five pages, made the pursuit real. Momentum started to build. Paul Eisenberg, who was a senior vice president of Global Medicine at Amgen, became a champion for the effort up through his retirement in 2018. Then Amgen’s current head of R&D Dave Reese became personally involved. Amgen CEO Bob Bradway was fully supportive of the initiative as well.

Funding followed. Amgen donated $2 million in 2018 to Lazarex Cancer Foundation’s Improving Patient Access to Cancer Clinical Trials program, which focuses on improving patient enrollment retention, minority participation and equitable access in oncology trials. The results of that grant included helping the program achieved 59% minority participation with 48% of participants coming from households earning $25,000 per year or less. It was spearheaded by Eduardo Cetlin, president of the Amgen Foundation.

“Clinical trials are critical to advancing new oncology treatments and can also serve as a lifeline for cancer patients who may only have a few options left,” Bradway said. “We are pleased to support the Lazarex Cancer Foundation’s efforts to create more equitable access to clinical trials for cancer patients and improve minority participation in clinical trials, regardless of their circumstances.”

But there was still a long way to go. And even though Amgen had begun to move forward in addressing the problem, it was the killing of George Floyd in the summer of 2020 and the subsequent Black Lives Matter movement that helped accelerate the push.

Racquel Racadio's document "Increasing the Diversity of Subjects and Investigators in Amgen Clinical Trials" became a foundation for the work of the RISE initiative that is aiming to tackle the problem of diversity in clinical trials.

Heightened Priority

Ponda Motsepe-Ditshego, executive medical director at Amgen and ABEN’s recently appointed Global Chair, revived ABENs efforts that were started in 2016 to push for more diversity and inclusion in clinical trials. Along with ABEN colleagues and with strong sponsorship from senior medical leadership – notably Amgen's R&D Head Dave Reese – she launched the newly-created team called Representation in Clinical Research (RISE) in October 2020.

She said the COVID-19 pandemic and ethnic minority communities being hardest hit, the killings of Breonna Taylor, Floyd and others along with the subsequent Black Lives Matter marches and Bradway’s email extolling the need to do better as a company gave RISE a “heightened priority.”

“It just made people and our industry more aware of what was needed,” she said. “But it’s important to note we began this work back in 2016 with people like Willis, Jude, Racquel and Mike Edmondson.”

Motsepe-Ditshego, a medical doctor by training, has been with Amgen for almost 10 years. She said it’s important to note there are recognized differences in the incidence of diseases among racial and ethnic groups along with differences in exposure or responses to medicines. A RISE document noting ongoing clinical and scientific data showed the prevalence of certain diseases disproportionately hitting minority communities, including cardiovascular disease, strokes, diabetes and several cancers, including colon, prostate, cervix and lung.

Ponda Motsepe-Ditshego, executive medical director at Amgen and ABEN’s recently appointed Global Chair, is leading RISE. She said RISE's three-year plan is making progress, but it will "take a village" to reach the initiative's goals. Photo: Amgen file photo

She said the RISE team will work with the Global Development Operations organization and other key groups by diversifying investigators and collaborating with those who serve diverse patient areas at clinical trial sites. They will also work with non-profits in communities that can help remove barriers to participation in clinical trials.

Some of the barriers, she said, include economic ones where residents in poorer communities often can’t get to distant sites or can’t afford to miss work to participate in trials. She also said it’s critical to work with influential community leaders to regain trust within communities who have been harmed by clinical trials in the past.

The most infamous of those examples was the Tuskegee Study.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the study – which ran for 40 years through 1972 – looked at the effects of untreated syphilis among Black men in Alabama. The study became unethical in 1940s when penicillin was determined to be the drug to treat syphilis but the men in the study were not offered the treatment. A class action lawsuit was settled in 1974 against the federal government for $10 million.

The lack of ethics in that study – along with others – fueled mistrust and an unwillingness of the Black community to participate in clinical trials for decades.

She said Amgen’s recent sponsorship of a conference hosted by the non-profit group Balm in Gilead, which has utilized local churches and community organizers to address health disparities in the African American community, is a move in the right direction. RISE plans to collaborate with trusted community and faith-based organizations like Balm in Gilead to assuage concerns about ethics in clinical trials.

Motsepe-Ditshego said the three-year plan of RISE is making significant progress.

But she also said there is more work to be done and that “it will take a village” to ensure success.

“It’s a journey,” she said. “It’s also the right thing to do.”

Footnotes

- Nuriddin, Ayah, Mooney, Graham, White, Alexandre, “Reckoning with Histories of Medical Racism and Violence in the USA” The Lancet: Oct. 3, 2020: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32032-8/fulltext

- Dornsife, Dana “Why I Started Lazarex Cancer Foundation:” https://lazarex.org/why-i-started-lazarex-cancer-foundation/

- Journal of the American Heart Association, May 19, 2020: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/JAHA.119.015594

- Global Participation in Clinical Trials Report, 2015-2016: https://www.fda.gov/media/106725/download

- Che, Caroline, Wong, Riley, “Black Patients Miss Out on Promising Cancer Drugs, Sept. 19, 2018: https://www.propublica.org/article/black-patients-miss-out-on-promising-cancer-drugs