Amgen Comments on ICER’s Proposed Changes to the 2020 Value Assessment Framework

OVERVIEW

Amgen appreciates the opportunity to comment on ICER’s 2020 Value Assessment Framework Proposed Changes. Our comments support the Framework’s evolution to align with scientific best practices and the relevant science-based, patient-centered foundational goals ICER itself has set forth. Amgen is a value-based company, deeply rooted in science and innovation to transform new ideas and discoveries into medicines for patients with serious illnesses. We hope ICER will carefully consider and incorporate our recommendations in an effort to achieve its aspiration of a more sustainable healthcare system for all patients.

We support the below goals ICER has stated for its Framework, and the current comment period presents an opportunity for ICER to deliver on these goals with aligned processes and methods:

- Support fair pricing, fair access and a sustainable platform for future innovation. “Ultimately, the purpose of the value assessment framework is to form the backbone of rigorous, transparent evidence reports that, within a broader mechanism of stakeholder and public engagement, will help the United States evolve toward a health care system that provides fair pricing, fair access, and a sustainable platform for future innovation.”1 In order to provide reports that are systematic, objective with clear guidance matched by results that are transparent, reproducible, credible and rigorous, ICER must adhere to the fundamental tenets of independence and objectivity, with greater balance between access, innovation and pricing.

- Align healthcare services with their true added value for patients and enable patient-centered care. “The framework also is intended to support discussions about the best way to align prices for health services with their true added value for patients.”2 While drugs represent approximately 14-17% of healthcare expenditure,3,4 health services including hospital, physician and clinical services represent more than half (53%).5 A broader focus on all health goods and services (not just drugs) will better enable ICER to inform healthcare value and sustainability.

- Reflect the experience and value of patients. “Even with its population-level focus, however, the ICER value framework seeks to encompass and reflect the experiences and values of patients.”6 Greater patient involvement in all parts of the assessment process, such as a long-term assessment that includes the patient perspective and enables patients to vote on treatment benefit, better represents the patient value. These require accounting for well-known and recognized gaps in patient data and disease epidemiology and inequalities in available treatments, access and ability to achieve a general level of good health.

Amgen’s main comments on ICER’s Framework are below and detailed in the sections that follow:

1) Incorporate changes to ICER’s Independent Voting Panel composition and voting format to be more representative and accountable to those impacted.

2) Include and quantitatively account for all relevant value elements and perspectives, including cost, cost savings and outcomes relevant to patients and their caregivers

3) Actively incorporate Real-World Evidence with greater weighting in the assessments

4) Include Adaptations for Rare Populations and maintain for Ultra-Rare Populations

5) Strive for processes and methods that are contextually appropriate for the US and avoid importing ex-US approaches based on different social and economic systems

1. VOTING PANEL COMPOSITION AND DELIBERATION PROCESS

| Incorporate changes to ICER’s Independent Voting Panel composition and voting format to be more representative and accountable to those impacted. |

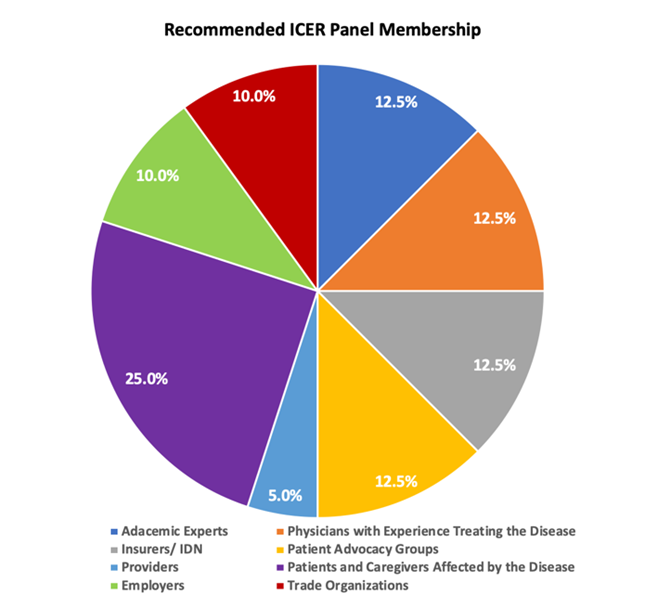

ICER’s Independent Panels should be representative and accountable to those that they impact with a meaningful representation in the areas of at least 15-20% of the panel discussants and votes. Anything less than this, risks continuing the current perception that ICER decisions are imposed on the most poorly represented group with the largest stake in the outcome. Past, present, and future patients and those who pay premiums to protect themselves in the event of disease pay for nearly all of health care through their taxes, wage concessions, copays, premiums, and out of pocket cash payments. Insurance companies, health care providers, manufacturers, policy makers and scientists are essentially trustees for the former group. With this in mind, people with an intimate connection to health care consumption for the ICER disease area at hand should have much more representation on voting panels that inform value recommendations than the current 3%.

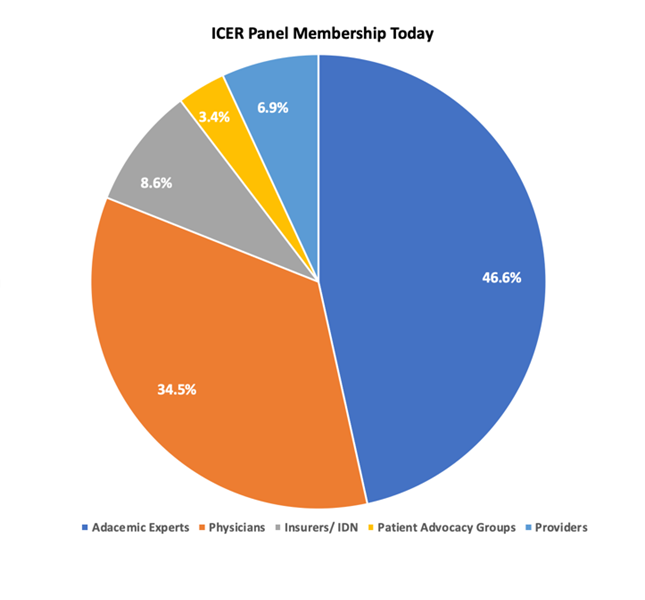

While ICER’s decisions have the largest patient impact, patients have the smallest voice across all panels and no representation on the Midwest CEPAC panel. Of the 58 members across ICER’s CTAF, New England CEPAC, and Midwest CEPAC panels, (19, 21, and 18 respectively), 47% is composed of academics, 34% physicians (all MDs that are not providers, public health/ health policy experts, payers, or epidemiologists), 9% payers and IDNs, 7% providers, and a mere 3% from patient advocates (Figure 1). At present, votes on value that could impact hundreds of thousands of patients are determined by less than 20 people lacking representative diversity to the populations they impact.

Figure 1: ICER Panel Membership Today & Recommended Membership

Amgen appreciates ICER is taking steps to optimize the conduct and deliberation of its panels with a Code of Conduct and encourage ICER to refine and enforce this new mandate. ICER should continue to use the code of conduct to ensure the perception of professionalism and objectivity during discussions and voting. In particular, ICER staff should be especially wary of influencing the relatively less expert panel members through leading questions, condescension (albeit inadvertent), failure to adequately justify and explain findings and provide counterpoints and disconfirming information, or statements that question or influence panel members voting. The code of conduct should equally apply to panelists, participants and the meeting moderator/facilitator. The moderator/facilitator, including Panel Chair, plays an important role in anchoring the discussion, framing the questions and guiding the votes, which needs to be managed as objectively as possible.

ICER’s lay-friendly seminars that provide background on evidence-based medicine to aid in assessments and better engage stakeholders should be led by external experts and patient advocates.7 We commend these seminars overall but more should be done to make them even more responsive to underrepresented stakeholders. ICER should allow patient advocates to lead these webinars to ensure patients gain a voice and are able to communicate their needs and priorities when voting on value for various diseases. ICER should consider collaborating with the National Health Council (NHC), who have specifically developed a tool to evaluate and maximize patient centeredness, the NHC Rubric to Capture the Patient Voice.8 This tool focuses on seven domains of patient centeredness: 1) Patient Partnership, 2). Transparency, 3). Representativeness, 4). Diversity, 5). Outcomes patients care about, 6). Patient-centered data sources and methods; and 7). Timeliness. Central to this Rubric is the co-development of solutions where patients are recognized as equal partners.9,10 ICER should consider applying this Rubric to ensure that patients and advocates do not feel like passengers in this process, but are active participants in developing appropriate methodology to assess treatment value and its implementation for each individual assessment ICER undertakes

2. PATIENT VALUE AND CONTEXTUAL CONSIDERATIONS

| Include and quantitatively account for all relevant value elements and perspectives, such as cost, cost savings and outcomes relevant to patients and their caregivers |

ICER should consistently incorporate the full disease burden to more holistically reflect the impact of a new health technology in alleviating this burden and improving overall health and economic outcomes. Disease burden includes the burden of out of pocket costs, lost productivity, emotional distress, and overall financial stress to the patient, their caregivers, families, and wider communities including employers, and society as a whole. Relevant stakeholder cost savings include non-medical costs, such as patient and caregiver out-of-pocket costs, lost productivity costs and impact on the health and wellbeing of caregivers and families. These should be included in a reference case, as is recommended by the 2nd Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine, which directs the capture of family and caregiver impacts.11

ICER’s Framework should actively supplement the QALY and evLYG, synthesizing the value from all relevant contextual elements and criteria and reflecting it in the numerical output of its analysis. ICER risks the integrity of its appraisal process by placing false precision on QALYs and willingness to pay (WTP) thresholds. QALYs elevate utility maximization above all other principles and are therefore a very rough and imperfect starting point for health care allocation. We don’t stop treating the very ill and dying in the US once they cross some arbitrary threshold for acceptable utility gains. evLYG is a good start towards looking at a broader range of alternatives, but this is utility by another name, and is not so different from the QALY in either principle or magnitude.

Until more measures gain familiarity and acceptance that reflect the additional values of equity, societal preferences, and other non-utility-based techniques, the QALY can be used as a starting point for HTA assessments, but assessment should not stop there. Research suggests that a flexible application of the QALY, including supplementing it with other elements of value, can help to account for its limitations in circumstances where a QALY is used.12,13,14 QALYs fall short in measuring small but meaningful health status changes, they are difficult to measure in those who cannot speak, are too young or very old and further QALYs are inconsistent across patients.15 ICER had previously experimented with a modified multi-criteria decision-analysis (MCDA) approach and should secure learnings from that experience with expert input to inform alternative approaches to robustly incorporate additional data with relevant weights.16 This is an evolving field and despite prior attempts to incorporate MCDA or other alternatives,17 a flexible, iterative approach may be needed until best practices are defined, enabling early patient preference and expert input to inform weighting across therapeutic areas, with full transparency.

ICER should engage in a stakeholder-driven deliberative process where all value elements are presented and considered by the panel before the vote on long-term value for money. While ICER panels vote on contextual considerations and other factors, ICER’s threshold guidance in deliberations translates to an insignificant role for these considerations. Part of the challenge is that stakeholder testimonials and other considerations are presented after the long-term value for money assessment has already taken place, and the Panel voting is guided by explicitly stated thresholds and quantitative values, which do not reflect alternative and potentially more expansive versions of valuation. This results in a vote solely determined by the quality adjusted life-year (QALY) with value empirically driven down by ICER’s guidance and restrictions.

Before 2016, QALY and threshold driven ‘low-value’ criteria were much less rigid. Pre-2016 ICER panels with more flexibility deemed seven out of 20 ICER drug assessments during this period, which came above the $150,000 threshold, as of largely intermediate value.18 With current ICER assessments, the opportunity for the panel to use additional evidence and considerations to vote on value for those treatments that are not ultra-rare and come above ICER’s 150,000 +25,000 threshold is impossible in practice. ICER should enable the voting panel to deliberate based on all available value elements (which should be incorporated early on in the assessment) and eliminate the automatic ‘low value’ (to payer) rating for values above the ICER threshold. This will enable ICER to secure a more equitable, informed, accurate and independent (albeit still estimated) vote on value.

3. REAL-WORLD EVIDENCE (RWE)

| RWE should be fully incorporated in future ICER assessments, including adjustment of RCT data where appropriate |

We appreciate ICER’s stated intent to leverage RWE data for new analyses to address key evidence gaps and strongly urge ICER to fully incorporate these data in its assessments.19 This includes adjusting the Evidence Rating Matrix with clearer guidance to accommodate greater availability of RWE and provide equal consideration with RCT data. As a fundamental principle, skillful health economics uses a majority of the data available to continually inform and modify estimates of the cost and outcomes of disease. Unless modified in its revised Framework, ICER’s current approach remains at high risk of imprecision and errors as it discards over 99% of data because it does not fit their criteria of “acceptable.” For a more accurate analysis, ICER must be willing to modify base randomized trial data with RWE estimates of disease prevalence, event rates, treatment use, population demographics, and other attributes of real-world clinical practice that provide a more relevant assessment of a new technology applied in a population health setting. Historically, ICER’s assessments have defaulted to clinical trial data over consideration for real-world data, selectively using RWE where clinical data were not available.20 Full incorporation of RWE in HTA assessments with greater weights provides a more holistic approach to healthcare cost sustainability. Payers already do this using actuarial analyses that account for differences between their insured population and data from other populations and treatment settings. ICER should be using RWE in this way as well. (Please see Appendix for additional supporting examples).

When analyzing uncertainty to guide panel deliberations, ICER should simulate only plausible scenarios instead of pre-specified analyses and adjust uncertainty over time with RWE. ICER proposes adding a new sub-section to voting, titled “Controversies and Uncertainties”, to explore conservative or optimistic model variations to acknowledge uncertainties and controversies raised by various stakeholders, while lending greater transparency to the rationale behind methodological decisions that underpin the base case.21 Typically reliant on modelling, ICER simulates treatment impacts over years, even decades; a process reliant on highly simplified use cases, structural assumptions designed to reflect future clinical practice and cost and efficacy assumptions derived from clinical trials, epidemiological studies and secondary sources. The amount of uncertainty can be staggering in an assessment and can never adequately be addressed by sensitivity or scenario analysis, which necessitates consistent and ongoing validation with real-world evidence.

ICER’s assessment timeline should account for RWE in support of its stated commitment to perform and incorporate relevant de novo data analysis, yielding more accurate results.22 Given increased availability, accessibility and speed of analysis, ICER has an opportunity to collaboratively incorporate relevant RWE analysis with relevant timeframe extensions. Similar to ICER’s proposal to increase assessment timelines for large drug class reviews,23 provisions should be built in that specifically addresses increasing the timeline necessitated to incorporate RWE that more accurately reflects the changing treatment paradigm. This is particularly important in areas for special populations such as pediatrics, rare disease and other vulnerable groups where accurate data representative of real-world clinical practice regarding disease process, disease state, QALY values and natural disease history are otherwise not available or are rapidly evolving.24,25,26

4. RARE, ULTRA-RARE & SPECIAL PATIENT DISEASE POPULATIONS

| Include Adaptations for Rare Populations and maintain for Ultra-Rare Populations |

Treatments for rare diseases should not be evaluated with the same value assessment framework as for common drugs. It is wrong to impose a pure utilitarian approach over the empirical economics of health care which attempts to justify a rigid threshold for utility-per-life-year-per-person, especially for rare disease. ICER states that there are “important equity concerns related to extending the threshold range higher for treatments just because they treat a small population”,27 but higher resource inputs for a minority is exactly the principle of insurance in general. Over a lifetime, most people pay more in insurance than they ever recover in paid benefits precisely because utility varies from person to person, disease to disease, with the truly unlucky receiving greater benefits. Rare diseases generally require the same degree of societal ingenuity, resources, and effort to develop new treatments or cures as common diseases, and the elevation of acceptable utility-per-life-year-per-person allows society to engage in these pursuits for the rare and unlucky. Patients with rare disease are born with inherently diminished chances of a healthy life compared to the general population – they lack the ‘fair innings’ of the majority of individuals.28 The equity concern that ICER describes for special treatment for a small population is intrinsic to the argument in that rare diseases do need to be assessed more discerningly and carefully than common diseases such as stroke or migraine.

Aggravating the imperfection of the QALY is rigidity regarding “thresholds”, which are particularly inappropriate for rare diseases. Patients with relatively rare illnesses, defined presciently by the FDA decades ago and still relevant today as starting at <200,000 cases nationally, are particularly disadvantaged when monolithic thresholds are applied.29 Defining the new standard of “rarity” as 10,000 or less is uncoupled from the reality of the larger per-patient investments required by government, industry, and society if we have any interest in equity towards those who are not fortunate enough to have a “common” disease. ICER should adopt accepted health economic practice which avoids providing a single, falsely precise answer to decision makers where there is inadequate knowledge to question it appropriately. ICER should also eliminate the 10,000 person threshold for rare disease until more objective research is available to quantify the relative increase in per-patient investments that are required for innovation in a given rare disease area. In ICER’s 2020 Framework, a standardized cost-effectiveness threshold will be used, from $50,000 to $200,000 per QALY/evLYG, for all diseases, from common to ultra-rare.30 If a threshold must be used, then it is becoming widely recognized that rare and health-catastrophic conditions should be judged against a higher threshold.31 A common threshold is not appropriate for rare diseases as these diseases are by their very nature, uncommon. In addition, the $200,000/QALY upper threshold can be expected to constrain access to rare disease treatments in the absence of published literature. This unfortunate categorization will essentially lead to most (if not all) interventions for these rare disease patients (with disease prevalence >10,000) receiving a ‘low’ value rating, without proper appraisal. At a time when fewer than 5% of the >7,000 recognized rare diseases globally still lack a viable treatment,32 this will likely have consequences in slowing the pace of scientific innovation necessary to prolong survival, improve quality of life, and potentially find cures for rare disease patients and their families. The updated Framework should align with the definitions and provisions in place to protect patients with rare diseases, including accommodation for the difficulty in designing, recruiting, and performing clinical studies.

ICER should change the Evidence Rating Matrix used for voting to reflect common or rare and ultra-rare disease prevalence categories. A fundamental issue with the guidance the voting panel receives on net health benefit is that the same Evidence Rating Matrix is used for common diseases as for rare disease despite the well-known challenges associated with collecting data, recruiting and performing clinical trials and unknowns in the natural history, epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of rare and ultra-rare disease. Also, the current approach places ICER out-of-step with the US regulatory framework, as the FDA relies on the ODA for its orphan designation.33 As suggested by HTA experts,34,35 ICER should accommodate for this critical area of difference in their preparation and rating of clinical benefit, which can have a profound impact on voting results. Moreover, ICER must consider the need for breakthrough therapies that the FDA has deemed of public interest to approve when accounting for uncertainty in evidence. Any breakthrough therapy that has received accelerated approval and or priority review from the FDA will often have limited clinical data with minimal long-term outcomes available. ICER should take into consideration that rare therapies will by their very nature have extensive uncertainty. Similar to changes in the voting and deliberation processes that ICER applies to ultra-rare disease treatments, ICER’s Evidence Rating Matrix should be updated to reflect well acknowledged limitations in rare and ultra-rare disease and look to global HTAs for reference. 36,37

5. U.S. CONTEXTUALLY RELEVENT METHODS AND PROCESSES

| Strive for processes and methods that are contextually appropriate for the US and avoid importing ex-US approaches that are based on different social and economic systems |

ICER should not adopt or map to foreign health technology assessment systems, as these are based on an entirely different healthcare environment than the US. ICER proposes to reference its evaluation of the evidence for added clinical benefit with the rating system used in Germany. While every HTA system has its strengths and weaknesses, they are designed to address the needs and constraints of the social and economic infrastructure within which they reside. Moreover, the considerable variation in HTA agency assessment of evidence demonstrates how context is fundamentally anchored to the empirical application of these techniques. The US healthcare ecosystem is a complex, multi-payer system with an inherently different infrastructure and context than Germany. In the German system, IQWiG provides a recommendation on the benefit at the request of the G-BA; however, in the end the G-BA makes the final decision which can differ from the IQWiG recommendation. Two separate studies demonstrate considerable variance in the evaluation of additional benefit for drugs in early benefit assessments (EBA) between IQWiG and the G-BA.38,39,40 While there may be opportunities to consider high level principles from other HTAs, it is critical to note that every HTA has its limitations and challenges, and the specific methods and processes employed by ICER must be contextually grounded to the US system. ICER’s step in evolving the way it rates evidence is important to securing wider applicability and acceptance of assessments, but any HTA technique must be designed to address internal validity, context, accuracy and flexibility in addressing the diverse needs not only at a national level but for individual communities.

CONCLUSION

Budget holders, decision makers and the stakeholders impacted by assessments can benefit if ICER focuses on key pillars of evidence, robust analytics, and the identification of areas of uncertainty. Health technology assessment should always be accompanied with a reasonable consideration of how Framework methodology impacts improvements in health delivery and overall healthcare outcomes.41,42,43,44,45 Thoughtful attention should further be given to the fact that at any given time we are all patients who will likely feel the impact of ICER’s assessments. Amgen appreciates ICER’s engagement of stakeholders in an effort to continuously update its Framework and urges ICER to create a 2020 Framework based on these recommendations, which are founded in guiding principles representing best practice and rigorous scientific methods. ICER has an opportunity to take a longer-term view of its role and command greater credibility by defining its role as one that offers guidance and informs payer decisions with a systematic approach to the evaluation of evidence with flexibility, inclusiveness, scientific integrity, transparency, and patient centricity, in the absence of absolutes.

REFERENCES

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 2.

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 2.

- CMS. National Health Expenditures 2017 Highlights. 2018. Link.

- Vandervelde A, Blalock E; Berkeley Research Group. The pharmaceutical supply chain: gross drug expenditures realized by stakeholders. 2017. Link.

- CMS National Health Expenditures, 2019 Altarum Institute, 2018.

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 3.

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 44.

- National Health Council. The National Health Council Rubric to Capture the Patient Voice: A Guide to Incorporating the Patient Voice into the Health Ecosystem Link

- National Health Council. The National Health Council Rubric to Capture the Patient Voice: A Guide to Incorporating the Patient Voice into the Health Ecosystem Link

- National Health Council. The National Health Council Rubric to Capture the Patient Voice: A Guide to Incorporating the Patient Voice into the Health Ecosystem. June 2019. Washington, DC. Link

- Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, Brock DW, Feeny D, Krahn M, ... & Salomon JA. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA, 2016; 316(10), 1093-1103. Link

- Neuman P, Greenberg D. Is the United States Ready for QALYs? Health Affairs. 2009 Oct. Link

- Pettitt DA, Raza S, Naughton B, Roscoe A, Ramakrishnan A, Ali A, Davies B, Dopson S, Hollander G, Smith JA, Brindley DA. The limitations of QALY: a literature review. Journal of Stem Cell Research and Therapy. 2016 Jan 1;6(4).

- ISPOR. ISPOR Special Task Force Provides Recommendations for Measuring and Communicating the Value of Pharmaceuticals and Other Technologies in the US, February 26, 2018. Link

- Pettitt DA, Raza S, Naughton B, Roscoe A, Ramakrishnan A, Ali A, Davies B, Dopson S, Hollander G, Smith JA, Brindley DA. The limitations of QALY: a literature review. Journal of Stem Cell Research and Therapy. 2016 Jan 1;6(4).

- Jit M. MCDA from a health economics perspective: opportunities and pitfalls of extending economic evaluation to incorporate broader outcomes. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation. 2018 Nov;16(1):45. Link

- ICER. Final Value Assessment Framework for 2017-2019. February 1, 2017. Link.

- Based on an analysis of all ICER assessments in 2016 from ICER reports and summary findings

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 6.

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 5.

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 22.

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 6.

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 39.

- Pollock, MCM. Real-World Evidence Studies. 2015. Link

- Khozin S, Blumenthal GM, Pazdur R. Real-world data for clinical evidence generation in oncology. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2017 Sep 13;109(11). Link

- Garrison Jr LP, Neumann PJ, Erickson P, Marshall D, Mullins CD. Using real‐world data for coverage and payment decisions: The ISPOR real‐world data task force report. Value in health. 2007 Sep;10(5):326-35. Link

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. 15.

- Farrant, A. (2009). The fair innings argument and increasing life spans. Journal of Medical Ethics, 35(1), 53-56. Link

- Global Genes, Allies in Rare Disease. (2015). RARE Diseases: Facts and Statistics. Link

- ICER. 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. August 21, 2019. p. ES3.

- Op. Cit. Garrison et al., 2019. Link

- NORD IQVIA Report. 2018. Link

- FDA. Designating an Orphan Product: Drugs and Biological Products. July 26, 2019. Link.

- Garrison LP, Jackson T, Paul D, Kenston M. Value-based pricing for emerging gene therapies: the economic case for a higher cost-effectiveness threshold. Journal of managed care & specialty pharmacy. 2019 Jul;25(7):793-9. Link

- Nicod E, Brigham KB, Durand-Zaleski I, Kanavos P. Dealing with uncertainty and accounting for social value judgments in assessments of orphan drugs: evidence from four European countries. Value in Health. 2017 Jul 1;20(7):919-26. Link.

- Garrison LP, Jackson T, Paul D, Kenston M. Value-based pricing for emerging gene therapies: the economic case for a higher cost-effectiveness threshold. Journal of managed care & specialty pharmacy. 2019 Jul;25(7):793-9. Link

- Nicod E, Brigham KB, Durand-Zaleski I, Kanavos P. Dealing with uncertainty and accounting for social value judgments in assessments of orphan drugs: evidence from four European countries. Value in Health. 2017 Jul 1;20(7):919-26. Link.

- Peinemann F, Labeit A. Varying results of early benefit assessment of newly approved pharmaceutical drugs in Germany from 2011 to 2017: A study based on federal joint committee data. Journal of Evidence‐Based Medicine. 2019; 12(1), 9-15.Link

- Ruof J, Schwartz FW, Schulenburg J M, Dintsios CM. Early benefit assessment (EBA) in Germany: analysing decisions 18 months after introducing the new AMNOG legislation. The European Journal of Health Economics, 2014; 15(6), 577-589. Link

- Peinemann F, Labeit A. Varying results of early benefit assessment of newly approved pharmaceutical drugs in Germany from 2011 to 2017: A study based on federal joint committee data. Journal of Evidence‐Based Medicine. 2019; 12(1), 9-15.Link

- Mason et al. Comparison of anticancer drug coverage decisions in the US and UK: does the evidence support the rhetoric? Journal of Clinical Oncology. July 2010.

- Bending MW, Hutton J, McGrath C, Comparative-effectiveness versus cost-effectiveness: A comparison of the French and Scottish approaches to Single Technology Appraisal, Monday May 17th 2010, ISPOR International, USA

- Access to innovative treatments in rheumatoid arthritis in Europe”, report prepared for EFPIA, October 2009

- Tim Wilsdon, Amy Serota. Charles River Associates. A comparative analysis of the role and impact of Health Technology Assessment. May 2011.

- O'Donnell JC, Pham SV, Pashos CL, Miller DW, Smith MD. Health technology assessment: lessons learned from around the world—an overview. Value in Health. 2009 Jun;12: S1-5.

APPENDIX

The full incorporation of RWE requires ICER to give greater weight to this source of data, going beyond simply validating select assumptions and enabling RWE to modify key drivers and results.

| Considerations of differences between RCT and RWE | Example |

|---|---|

|

There are marked differences in estimates from RCT data and real world clinical practice, which has dynamic, heterogenous settings. |

In the area of bone fractures in patients with cancer metastasis, RWE of higher fracture rates seen in clinical practice necessitates adjustments to clinical trial evidence in any HTA assessment. 45

|

|

Important counter-intuitive differences with serious impact on patient outcomes can be uncovered as clinicians decide how they utilize new treatments in their practice. |

E-cigarettes were assumed to increase likelihood of quitting; however, a systematic review of 38 studies showed exactly the opposite: the odds of quitting cigarettes were 28% lower for individuals who used e-cigarettes compared with those who did not. 45 |

|

Safety can differ significantly from trials to real-world practice. |

Trials in anticoagulant-naïve patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) treated with dabigatran etexilate raised concerns on bleeding events and myocardial infarction (MI); however, a follow-up registry data analysis of nearly 14 thousand patients showed bleeding rates were comparable and mortality, intracranial bleeding, pulmonary embolism, and MI were lower with dabigatran. 45 A publication of a meta-analysis of twenty-three thousand patients demonstrated a significant real-world increase in MI for rofecoxib versus placebo, leading to one of the most well-known drug withdrawals involving rofecoxib. 45 |

|

Costs can change significantly from models of long-term cost-effectiveness analysis when validated in real-life clinical settings. |

In a study on the real-world practice of schizophrenia treatment, the average annual costs per patient for an atypical antipsychotic was 16% of the costs in published trials. 45

|