Xinghua Pan was in the woods, looking at the dead woman’s body. It had been deteriorating for a few days in the fall of 2008. She had been assaulted, killed and taken there to be dumped.

“The smell stayed with me,” Pan said. “I had to discard my clothes after being on the scene.”

But Pan put that aside and went to work.

As the forensics lab officer with the Singapore Health Sciences Authority’s Criminalistics Lab, he began to help detectives piece together what happened to the woman in her last moments. The crime scene was cordoned off and Pan’s team began the investigation searching for trace evidence that might eventually lead to an arrest.

Early on, he said, there weren’t many clues to be found. But then came a break.

Investigators with Pan discovered very small flecks of paint on a nearby tree. It became clear that the perpetrator had backed the victim’s car into it before leaving the body.

The paint chips were gathered as evidence, taken to the lab and examined through powerful microscopes. They were then tested to determine the exact color and type of paint used for the car. Pan said the samples were cross matched to a data base of automobiles manufactured with that color and style of paint. Eventually, the team narrowed it down to one model of car.

It ultimately led police to the vehicle and the arrest of the assailant, who was tried, convicted and eventually found guilty of the murder.

“It helped knowing the work I did actually provided an answer and, hopefully, some resolution to the family,” Pan said. “It brought accountability and that someone had to answer for the dead.”

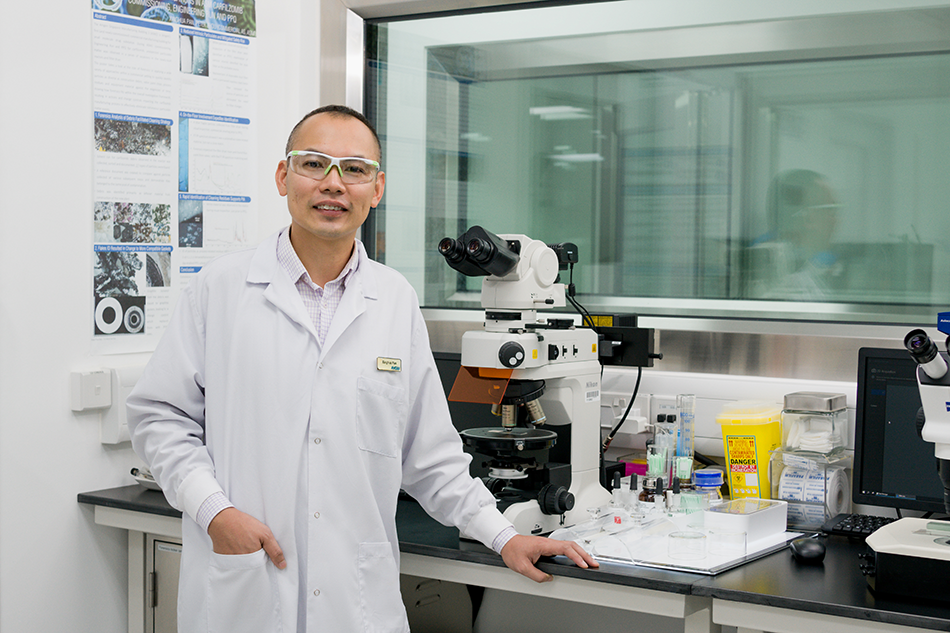

Xinghua Pan, a Process Development scientist, at Amgen's Singapore site. Photo: Franz Navarrete/Getty Images for Amgen

But with each case Pan helped crack with the forensics team, he also thought more about the help he was offering and how it came too late for the victim and their families. Yes, he could provide some answers about the tragedy. And he certainly was a key step in providing the victim’s family a sense of closure and a measure of justice. Still, he sometimes wondered what it would be like to use his skills when it wasn’t too late to save someone.

Seven years ago, he got an answer.

Pan recalled an Amgen representative approached him and asked if he’d like to come work for the biotech company and help them identify microscopic problems during the drug-making process in order to ensure medicines were safe when they were given to patients. Pan thought about it and soon made his decision.

He said it sounded great.

‘Solving a Mystery’

Pan is part of a team of about 14 forensic scientists working at Amgen across five sites globally that are charged with identifying any problems that might impact medicines manufactured by the company.

Pan’s site in Singapore can investigate any steps in manufacturing but the primary ones he sees from the site there include medicines for patients with serious illnesses such as cancer, osteoporosis and migraines.

The largest forensics lab in the Amgen network is in Thousand Oaks, California but the sites in Puerto Rico, Rhode Island, Ireland and at the upcoming site in North Carolina also have access to some of the most cutting-edge microscopes that can identify issues not visible to the naked eye.

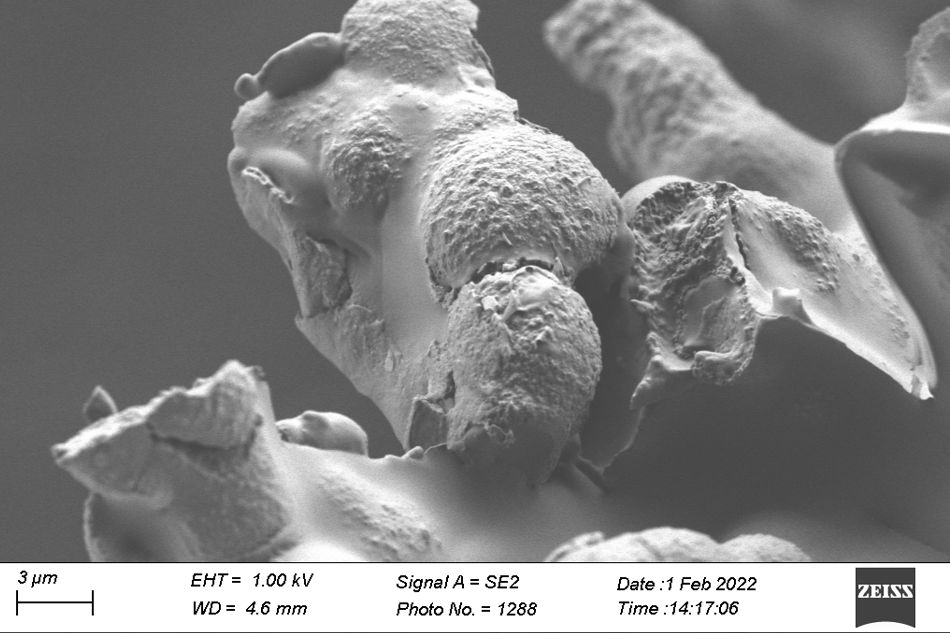

The power of some of those microscopes is so great that when tiny cell or foreign fragment is placed under it, the image generated looks like abstract art, a psychedelic concoction from the children’s book author Dr. Suess or a series of science fiction landscapes. To demonstrate the power of its most powerful microscope, the team’s scientists once placed a fly under it, magnified it 10,000 times and the result looked like a creature from a horror film.

Image of debris believed to be cellular. Photo: Amgen Forensics Lab

Robert Soto, who heads up the forensics team in Thousand Oaks, said most of their investigations center around particles in solutions, but can also include particles or buildup on manufacturing equipment or consumables such as filters, inhomogeneities on drug product tablets, discolored particles in raw material drums, and defect analysis on single-use bags or storage containers.

“It’s a lot like solving a mystery,” Soto said. “Something happens – typically a foreign substance is detected – and it comes to us and we are tasked with finding, characterizing and identifying the material, which is key to determining the origin of the issue, assessing it and helping to resolve it.”

Pan said the process of placing his eye to the microscope and seeing substances magnified thousands of times bigger can feel like a journey into a different world. But being immersed in this virtually invisible world also makes the outside world clearer.

He said it leads to piecing together how things work and finding possible causes for problems because the world is more than what can be seen.

David Semin, executive director of Process Development at Amgen, said the team has done outstanding work.

“The strength of Amgen’s forensics differentiating capability is attributed to the staff’s diverse expertise and their ability to efficiently solve problems,” Semin said.

Evidence Intake

The process of requesting an analysis by the forensics lab is standardized, Soto said. Ensuring end-to-end quality and compliance is a foundational part of the forensic platform at Amgen.

Anyone at Amgen, or even contract organizations that work with Amgen, can complete a submission form that details the observed problem and requested analysis, such as identification or sizing of unknown material. Forensics staff receive the samples and perform intake imaging, capturing the state of the sample before it is altered.

Pan said it’s similar to a crime scene – when taking in evidence it’s important not to disturb it so as to get a more accurate analysis of what happened.

Intake kits are the first step in the process of recovering and identifying microscopic problems investigated by forensic scientists. Amgen file photo.

The scientists will then go through the process of isolating the particles, which can be tricky and require a steady hand. Particles suspended in solution can be retrieved using sharp tungsten microprobes and transferred to a new surface for further analysis. Or a particle in solution can be recovered by filtration, which separates the solid from the surrounding liquid.

That’s when eyes get to microscopes for imaging of the particle using optical stereomicroscopy after isolating the particles to get accurate dimensions, shape, color and other attributes under magnification that will help crack the case.

Scientists will also use Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy that provides a “molecular fingerprint” of the unknown material that can be used with commercial databases to unambiguously identify organic materials.

Soto said particles may require characterization of elemental composition if they are primarily inorganic and sometimes the scientists will use a combination of scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy to visualize the topography of particles and determine elemental composition.

The Curious Case of the Mystery Glove

Pan said he remembered a case he investigated that a drug substance bag with a mysterious defect that rendered it unsuitable.

The problem? Not all the bags on the production line shared the same defect.

“It really wasn’t clear at first what might be causing this,” Pan said.

Pan said they examined an intact bag. Then compared it to a defective one. To the visible eye, they appeared the same. But after a battery of tests, studying it under polarized light and microscopes, a fold not visible to the naked eye appeared on the defective bag.

But what was causing the fold, Pan wondered.

“We went to the manufacturing site to see what could match up with that fold,” he said. “That’s when we saw the tubing that is inserted in the bag was creating the crease that was leading to the defect.”

Soto said that case was studied by the team and that all the information gleaned from each case can help inform solutions to subsequent cases. He said it’s often not just looking through the microscope but partnering with the experts on the manufacturing teams and looking further up in the process and to consider scenarios that might not be thought of as suspect initially.

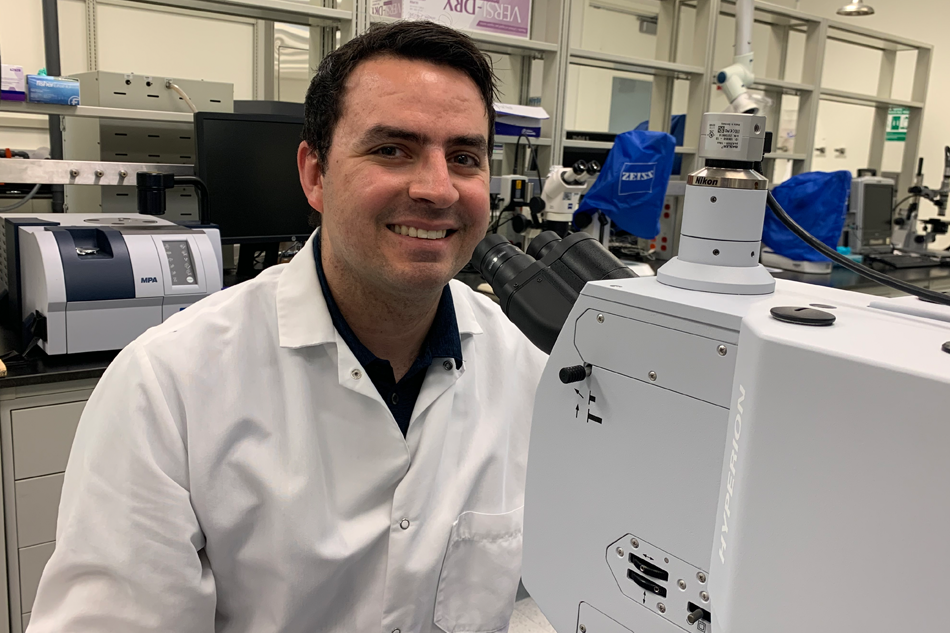

Robert Soto, a Process Development senior scientist at Amgen's Thousand Oaks site. Amgen file photo

He recalled a case where strange, black particles were found in a small molecule drug product while the material was being blended with other components to make the drug product tablets.

Initially, through the use of Fourier-transform infrared microscopy, the material was identified as rubber. But he said they still had to narrow it down to a specific type of rubber so it could be cross matched with any kind of rubber that the product might have encountered along its journey.

The investigative process ultimately led to the culprit: particles of brominated butyl rubber from a specific type of glove that was used at a different facility on a different continent.

“I think the staff in Amgen’s forensic network come in every day for the science and we love mastering our use of scientific equipment for real life problem solving,” Soto said. “It’s extremely gratifying to see a direct link between our work in the laboratory and the impact on Amgen’s patients.”

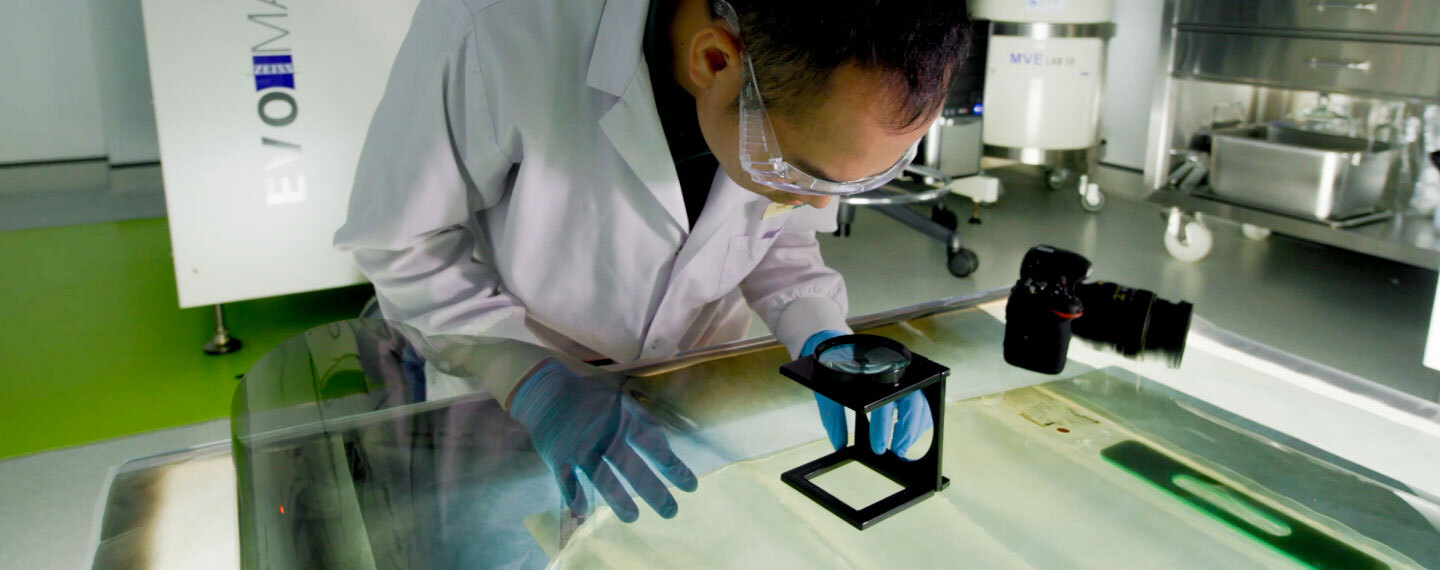

Xinghua Pan studies microscopic particles at the forensics lab in Singapore. Photo: Franz Navarrete/Getty Images for Amgen

‘More Hopeful’

Pan said being a few years removed now from his years working crime scenes and instead diving into the microscopic world of biotech medicines has been a welcome change.

Before, he said, he remembered the weight of what he would see at crime scenes could bring him down at times. He would escape into doing art or reading. He still does those things, but they feel more liberating now.

“I have lightened up a lot more personally since coming here,” Pan said. “It’s a different environment. I’m not surrounded by death all the time. You aren’t confronted on a daily basis with the depravity humanity is capable of. The work I do here feels just as challenging, but also more hopeful.”

The focus of his work has changed. So has the scope. And what he sees now through the lenses in Amgen labs offer a fresh perspective mostly missing from his days investigating homicides.

These days, his focus is on life.