Shamel Riley walked into the room set up with round tables and settled into a seat near the window while her teenage son, Raymond, grabbed some food set out at a nearby table.

Outside the open doors of the Culver City Teen Center in Southern California, a loose-knit group of players practiced on a softball field. A few sat on grass, watching. A family celebrated a birthday as balloons danced in a slight breeze.

It was a Saturday afternoon. Raymond normally would be hanging out at home, maybe studying or playing video games. She would likely have been at her other son’s baseball game.

But not this Saturday. This was too important. This was about the future.

“My son is going to be the first Black male to go to college and graduate in the family,” she said. “That’s why we are here now.”

The room continued to fill up.

Parents, guardians and teenagers took their seats while the staff of the nonprofit Educating Students Together checked people in.

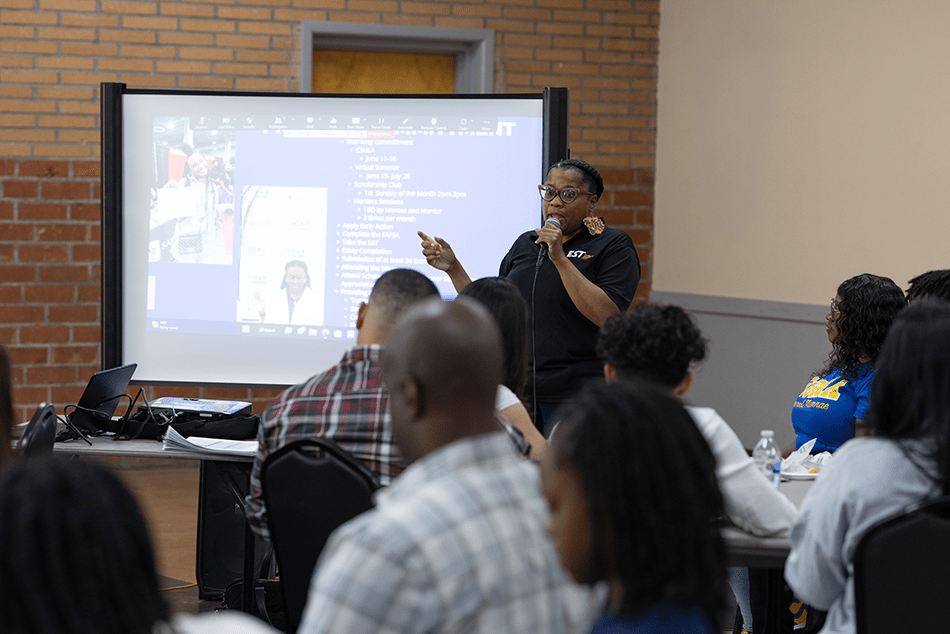

Two women in black polo shirts finished setting up the projection screen. There was a hum of conversation in the room as several dozen people ate sandwiches and chips. A few pulled out pens and paper while others prepared to record on their phones the information about how to navigate the college application and scholarship process.

The screen lit up with a QR code. Hands holding phones shot up in the air to scan it. Gina Lutcher, who heads up the Foster Youth Program for Educating Students Together, got right into it.

“We’re going to hit the ground running,” she said. “I’m about to shake your whole world.”

Watching Lutcher as she worked through the presentation was Yasmin Delahoussaye. It was just three years ago that she had little reason to believe this day – let alone this moment – would actually come.

Future college students met in Culver City, California for the orientation session put on by the nonprofit Educating Students Together.

George Floyd Murder and Aftermath

Delahoussaye remembered seeing the video of George Floyd being murdered on May 25, 2020.

For almost nine minutes, the video showed a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck while he kept his hand in his pocket. The officer stared impassively at the cell phone cameras recording him as bystanders begged him to stop. Floyd begged the officer repeatedly to simply let him breathe.

Then Floyd said: “Momma, I love you. Tell my kids I love them.”

Those words shook Delahoussaye.

“I didn’t know his life was going to be snuffed out in nine minutes,” Delahoussaye said. “But when he called out to his mother, that was the point I knew he was going to die.”

The aftermath of Floyd’s murder was a seismic event that rocked a nation and drew renewed attention globally toward calls for social justice, racial equity and an end to police brutality.

Protests went on for days in cities across the country and around the world. It was a reckoning that was being compared to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. At George Floyd’s funeral on June 4, Rev. Al Sharpton told mourners: “As we lay you to rest today, the movement won’t rest.”

Delahoussaye certainly wasn’t going to rest – even as Educating Students Together, her nonprofit that had made it a mission to get Black teens scholarship money to go to college and graduate, was on the brink of closing down due to a lack of funds amid the pandemic’s impact on philanthropic giving.

“Nobody was giving anything,” she said. “Then George Floyd happened.”

Her organization became a member of the Black Equity Collective, a Southern California-based intermediary organization founded by Kaci Patterson. Delahoussaye applied for a grant.

The Collective aims to strengthen and grow Black-led and Black-empowering organizations in a variety of issue areas. She received funding to support her work and invest in the organization’s long-term sustainability with a grant provided, in part, by the Amgen Foundation.

“It was like a prayer had been answered,” Delahoussaye said.

Yasmin Delahoussaye, founder of the nonprofit Educating Students Together. Mark Von Holden/Getty Images for Amgen

Long-Term Impacts

Patterson called it “a large awakening” in the world of philanthropy immediately after Floyd’s murder.

“There was this scramble to find ways to contribute and be a part of the solution,” Patterson said. “Funders said we need to be better with Black-led organizations and can you help us with that?”

Begun as a pilot project in 2017 – known as the Black Equity Initiative then – Patterson said in the months before the Floyd killing in 2020, they had been looking at ways to gain long-term sustainability to help its targeted causes.

It was the kind of organization Scott Heimlich, president of the Amgen Foundation, knew could have an outsized impact. Since 2020, the Amgen Foundation has given the Black Equity Collective more than $100,000. Overall, the Foundation has given $11.5 million to nearly 100 nonprofits focused on social justice and equal opportunity, as well as partnering with groups such as the Amgen Black Employees Network (ABEN) to advance many grants.

“The Black Equity Collective is focused on strengthening the long-term capacity of Black-led social justice organizations across Southern California,” Heimlich said. “Our support for the Collective is just one component that makes real our commitment to diversity, inclusion and equity, and ensures that all communities benefit from the leaders within advancing social change.”

Denzel Tracey, senior associate of sourcing excellence at the Amgen Capability Center (ACC) in Tampa Bay, said the donations made by the Foundation – along with a willingness to discuss the issues of diversity, inclusion and equality openly in the wake of the Floyd murder has him more hopeful.

“That’s the biggest change I’ve seen,” said Tracey, Amgen Black Employees Network chair for the ACC. “To see a concerted effort by a corporation to talk about what Black people are experiencing outside of work and how that might affect what they are doing at work – that’s huge progress. There’s more work to be done, though. It’s really important for Black kids growing up to see other people who look like them and share cultural similarities doing things that are going to put them in a positive position and graduating from college is very important because each graduate becomes a pillar for future generations in that family.”

Patterson said it’s the long-term view that needs to drive philanthropy as that leads to lasting change. She said three years after the Floyd killing, it’s been a mixed bag of results.

“There is a heartening and disheartening answer. The disheartening answer is we still have to make the case and have to convince people of the rightness of investing in Black-led organizations,” Patterson said. “The heartening part is I’m still seeing – in philanthropy anyway – a continuing commitment to the journey against racism.”

Delahoussaye believes the journey begins with education. She knows the money that came from the Amgen Foundation, which came to the Black Equity Collective which, in turn, went to Educating Students Together has been key in keeping them afloat.

The result?

In the past three years, about 500 students have gone to college and Educating Students Together helped students last year alone obtain $4 million in scholarships.

Taking notes at the orientation for future college students in Culver City, California by the nonprofit Educating Students Together. Mark Von Holden/Getty Images for Amgen

‘Black Excellence is Real’

Zach Carter was one of those 500 students supported by Educating Students Together.

He had just finished his freshman year at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona this month and found himself on a Saturday afternoon sitting with his younger sister, Madison, in hopes of helping her get to college.

Carter said he’d been in three different foster homes since he was 12 and the only reason college was even on his radar was because his sister – who is six years older than him – got financial assistance and went to college. She encouraged him to do the same by going through Educating Students Together.

But even with her encouragement, he found himself slipping with grades in his freshman and sophomore year of high school. Living in Compton and taking the bus each day to school – sometimes a two-hour trip – was difficult. The foster homes he was in didn’t offer much help or direction for his future.

“It wasn’t easy, but looking back, I would say it’s about not giving up,” Carter said. “No matter where you are, you don’t have to stay in that position. I try to always think positive and that helps. But you also need a support group.”

Delahoussaye sees her organization as exactly that.

“The average family we work with is making less than $40,000 a year in Southern California,” she said. “I don’t even know how you survive on that, let alone add in the price of college. But that’s why we are here – to help and support the students and disrupt generational poverty.”

At the break, with Lutcher and others going over the details of a week-long college orientation plan for the soon-to-be college students, Delahoussaye saw Carter and the two hugged. She smiled and he told her about how school was going.

He was studying landscape architecture and wanted to gradate and work in beautifying public spaces. Madison, holding a book, wasn’t sure what she was going to study yet. But she was motivated to follow in her brother’s footsteps and get to college as well.

Yasmin Delahoussaye, founder of Educating Students Together, shares a moment with Zach Carter, who went through the college prep program more than a year ago and is now in college. Mark Von Holden/Getty Images for Amgen

Stories like that are what drives Patterson – even more so three years after the Floyd murder.

She said she never watched the video of him being killed. Patterson has known people who died due to violence. She said she didn’t need to see video to know Black pain is real. And she worries sometimes that is often all people see.

“Black joy is real. Black resilience is real. Black excellence is real,” Patterson said. “We need to see more of that. To pass on the spirit of Black possibility and believe in Black possibility.”